Why Is Reflection So Hard, Even When Everyone Agrees It Matters?

Everyone agrees—at least on paper—that teachers must be reflective practitioners. Teacher education textbooks say it. Research reiterates it. Policies assume it. Workshops celebrate it. Reflection is often presented as the bridge between experience and growth, between practice and improvement. A teacher who reflects, we are told, will automatically become a better teacher.

And yet, when reflection moves from theory to daily practice, something quietly breaks.

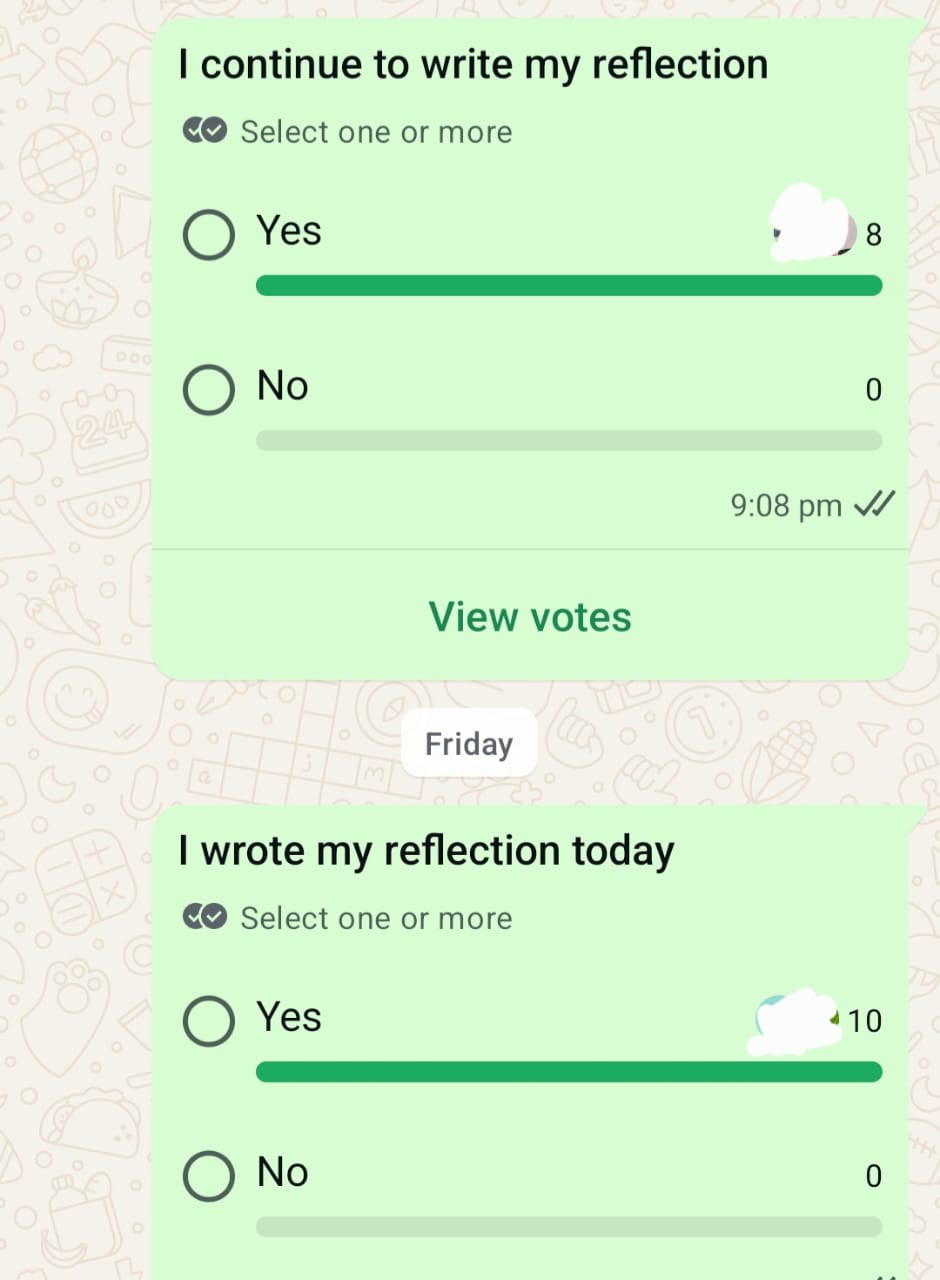

Over the last few weeks, I have been supervising some teacher trainees during their School Experience Programme. I insisted that they maintain a daily reflective journal. To support this, I put out a simple daily poll—did you write your reflection today or not? No one was asked to share what they wrote. The intention was not surveillance, but habit-building. What emerged was revealing.

Responses fluctuated. Some days many wrote, some days very few. Silence was more common than refusal. Almost no one said, “I will not write.” But many simply did not respond. When I asked a few of them in person—Have you written your reflection?—the answer often came hesitantly:

“Sir, last three–four days se nahi likha.”

This moment is worth pausing at.

Because technically, many of them do write—once in a week, sometimes even later—often compiling several days together. On paper, the task gets completed. The box is ticked. But pedagogically, this is not reflection; it is a chore. It is post-facto documentation, not thinking-in-action. It records experience but does not work on it. Reflection, if it is to serve its purpose, has to be closer to the moment of teaching. It has to catch the discomfort, the confusion, the small failure, the unexpected response of a child—while it is still alive. When reflection is postponed, it loses its edge. It becomes neat, polished, and strangely safe. And safe reflections rarely change practice.

What the inconsistency in my students’ writing reveals is not laziness or lack of seriousness. It reveals something more uncomfortable: they do not yet see a direct link between daily reflection and change in their teaching–learning process.

For many novice teachers, school experience is about survival. Managing a classroom, following instructions, completing files, responding to authority—these take precedence. Reflection demands something else. It demands distance from action while still being inside it. It asks teachers to look at themselves, not just at children. That is not a neutral act. It is emotionally and cognitively expensive. There is also an identity issue at play. Most of our teacher trainees come from educational cultures where being a “good student” meant completing tasks correctly, not questioning oneself deeply. Reflection disrupts this identity. It asks: What confused you today? Where did you fail? What troubled you? These are not questions our schooling systems have trained students to answer honestly. So silence becomes a strategy. Not writing becomes easier than writing something that feels inadequate, repetitive, or too revealing.

Daily reflection also challenges another deeply ingrained habit: we are used to reflecting after events—after exams, workshops, inspections—not during everyday practice. Micro-reflection feels artificial at first. “Nothing special happened today,” some say. But it is precisely this “nothing special” where teaching actually happens. If reflection is reduced to a weekly or monthly ritual, it loses its transformative potential. It may help us remember, but it will not help us change. Reflection is not meant to be an archive of experiences; it is meant to be a tool for adjustment—small, daily, sometimes uncomfortable adjustments.

The struggle my trainee teachers are facing is, therefore, instructive. It tells us that reflection cannot be assumed simply because we value it. It has to be taught, scaffolded, normalised, and protected from becoming a performative task. It requires psychological safety, time, and a belief that thinking about today can actually make tomorrow different. Perhaps the real question is not why students are inconsistent, but why we expect reflection to come easily in systems that rarely slow down enough to think.

If we want reflective teachers in classrooms, we must first accept this truth: reflection is hard because it asks teachers to sit with uncertainty—and uncertainty is something our education systems are deeply uncomfortable with.

- Log in to post comments