Reading Between the Lines: Textbooks as Mirrors of Society

This week, I took my class on Textbook Analysis. It was the first time these trainee teachers were expected to look at a textbook not as students, but as analysts.

I began with a simple question:

“How many of you have seen the textbook?”

They smiled — almost every hand went up.

“How many of you have used it?”

Again, most hands were raised.

“And how many of you have read it cover to cover?”

This time, only a few hands stayed up. The room filled with laughter and confessions.

One student said, “Sir, chapters that are not part of the exam syllabus — we don’t read them.”

Another added, “The ones written inside the box with the note ‘only for reading’, we skip those too.”

Their honesty opened the real conversation I wanted to have.

I asked, “Which chapter gets dropped from the syllabus? Which content gets boxed as ‘only for reading’? And who decides what stays and what goes?”

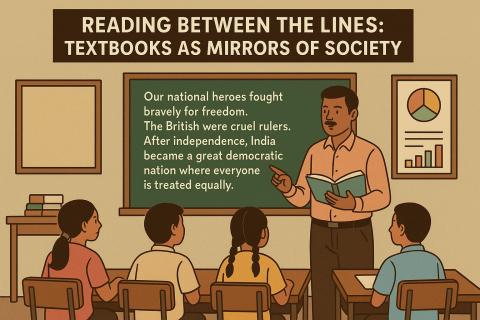

The analysis of educational textbooks, often perceived merely as an academic exercise involving checklists and reports, is fundamentally about developing the capacity to see the invisible threads of society woven into familiar learning materials. When we open a textbook, we must ask whose voice is truly being heard—is it the teacher’s, the author’s, the policymaker’s, or the state’s, speaking softly about what counts as 'knowledge'? This inquiry underscores a vital truth: textbooks are never neutral. They function as political documents disguised as innocent learning materials, carrying the soul of a society—its values, hierarchies, silences, and hopes. Indeed, if education reflects society, the textbook is the place where that reflection becomes most visible.

The central task in analyzing these texts is to become a critic, moving beyond the role of a consumer. This involves learning to listen to the hidden narratives that flow from the book into the classroom and quietly into children’s minds. For trainee teachers, this process demands a layered approach, examining four key dimensions present in every textbook.

First, the philosophical layer asks what idea of education lives within the text—does it promote obedience and memorization, or does it encourage questioning and exploration? For instance, a moral science textbook glorifying obedience to elders reflects Idealism, whereas a social science chapter encouraging group discussions carries the spirit of Constructivism.

Second, the psychological layer addresses how learning is imagined. A book emphasizing drills, repetition, and fixed answers often mirrors a behaviorist model, while one that encourages children to observe, think, and connect is shaped by cognitive or constructivist thinking.

Third, the sociological layer scrutinizes representation. This lens questions who is visible and who is missing. It reveals the hidden curriculum—the unspoken lessons conveyed about gender, caste, religion, and power. For example, a text that consistently portrays fathers as breadwinners and mothers in kitchens repeats social stereotypes.

Finally, the socio-political layer focuses on the subtle expression of grand narratives like nationalism, morality, and development. When a textbook claims "we all are equal" while ignoring social inequality, it not only reflects the state’s imagination but actively reinforces it. Once a narrative gains entry into the textbook, it gains legitimacy and becomes accepted as truth in the classroom.

In reality, the world of knowledge is vast, but textbooks, like a shopkeeper's display shelf, present only selected and carefully arranged items. While the ideal purpose is to spark enough curiosity for students to explore the knowledge that remains "packed away", classrooms often train children to look only at what is displayed, examinable, and part of the test. The irony is evident when students admit they skip chapters outside the exam syllabus or content boxed as ‘only for reading’.

This shift demonstrates that the goal of education has often been misplaced: what was meant to be "taste"—a spark for exploration—was misunderstood as "test". Textbooks, meant as a doorway to curiosity, have become a checklist for examination and a tool to measure performance. This debate is historical, as even Gandhi argued against over-reliance on textbooks, believing they "enslave the teacher" by shrinking their world to what is printed on the page. However, since textbooks provide essential structure and are often the only book millions of children in the country own, the solution is not rejection, but critical reading.

The ultimate aim of textbook analysis is not fault-finding, but truth-finding. By identifying the underlying philosophy and sociological stance, future teachers are empowered to reclaim agency. They must reflect on how they would teach a chapter differently, challenging what the text says—or fails to say—by the methodology they employ. The purpose is not to merely fill minds with content, but to awaken them to context. When students realize a textbook can hide so much meaning, they recognize that the classroom is the world concentrated between the covers of a book. What we choose to see in that mirror determines the kind of classrooms, and ultimately, the kind of learners, we build tomorrow.

- Log in to post comments