Role of Children’s Write-ups in the Teaching and Learning of Social Science: A Pedagogic and Curricular Intervention

SYNOPSIS

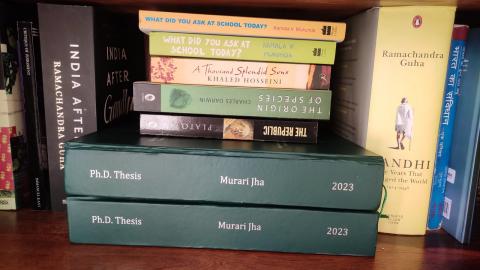

of the Ph.D. Thesis

Abstract

When I am writing this thesis, the world is witnessing a depletion of democratic values across the globe. The more we lose ground to authoritarian regimes, the more difficult life becomes for the general populace. In such an anti-democratic environment, this work sheds light on the daily life struggles of ordinary people. It talks about a pedagogy that enables children to raise questions and resist injustice. As Moreira & Diversi (2022) posit “We have been teaching, writing, and collaborating, believing that ‘[h]ope is an ontological need’ (p. 8), perhaps even more so now that many democracies are experiencing a return to populist nationalism. These are filled with intense and overt exclusionary narratives and unfriendly walls, founded on ideologies and narratives that intensify notions of Us against Them along ethnic, gender, class, sexual orientation, (dis)abilities, religious, and immigration status lines.” I see this work as a pedagogy of hope, which is relevant across the boundaries of time, space, and disciplines. After all, the pursuit of justice and equality has been a constant search for communities across the globe. But this pursuit is not easy. The structure that perpetuates injustice and inequality is rigid and governed by a set of hegemonic ideas. To challenge it, one has to understand the knowledge systems that enable such a structure.

My work is based in a Delhi government school, demonstrating how education can function as a powerful tool for resistance. It empowers students to question and push back against the status quo that perpetuates social reproduction. In the School, section 9D was allotted to me to teach social science. In this class, there were a few students who were not promoted to the next grade. In all the sections put together, approximately 50 percent of students had failed in grade 9. In discussions with teachers, it was revealed that students were unable to write anything on their answer sheets, and therefore, teachers felt helpless. It was inferred that if the students had written at least something on the answer sheet, teachers could have helped them pass. The most significant challenge identified by the teachers was that the students lacked adequate writing skills. I found myself standing in section 9D, in a school where the sections were segregated based on academic performance. Section A was for the English-medium students, considered as academically “good.” I was allotted section D, which was designated for those students who were not performing well. For almost a decade now, I have been deeply engaged with the world of academics and theories of Education. I completed my Masters Education in 2014, from the Tata Institute of Social Science (TISS), Mumbai, a premier institute for higher education in India. Between 2013-14, I was also a Teacher Fellow at the Regional Resource Centre for Elementary Education (RRCEE), CIE. My theoretical engagement served as the catalyst for me to perceive the current situation, where a significant number of students were failing due to inadequate writing skills, as an opportunity for me to bring about some positive change. Darling-Hammond (2017) discusses how engaging with theoretical frameworks and concepts helps teachers develop a deeper understanding of effective teaching strategies. Hattie (2009), in his book "Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement," states that one of the key findings of his work is the importance of teachers' theoretical understanding and knowledge of effective teaching strategies. Shulman (1986), in his seminal article, “Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching” discusses the concept of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) and its role in effective teaching, emphasizing the need for teachers to engage with theoretical frameworks and concepts to enhance their pedagogical knowledge. Cochran-Smith and Lytle (1999) explore the relationship between teachers' knowledge and their classroom practices. The authors argue that engaging with theoretical frameworks and concepts helps teachers critically analyse their own practices, identify areas for improvement, and make informed decisions about instructional methods and approaches.

In this context, I introduced a daily ritual of writing a page. Initially meant to develop writing habits among students, this practice opened a whole new world of possibilities to the extent that I decided to pursue it as my Ph.D. research in 2017. I was able to see my practice in the light of the theories that I have learnt. It enabled me to see the links between what children wrote and what the Social Science Curriculum prescribed. I found that it even challenged and extended the idea of curriculum in social science, leading me down a path where I was experimenting with a new pedagogy. I was also amazed at how these children, otherwise labelled as low-performers, were actively creating knowledge. For my Ph.D, I started working with the students of grade 7 and continued until they passed out from grade 8. In terms of the number of months, I was engaged in the field for around 15 months from December 2018 to March 2020. During which I made the intervention of helping the children write and discuss their write-ups and recorded my observations. I also want to highlight that my general engagement with the field has continued for 12 years. The reason I want to emphasize this is that many nuances I capture here or insights I develop come from this long- term engagement with the field.

The work is rooted in my decade-long practice as a teacher. After teaching for 5 years, I began to see my practice in the light of various theories. Continuously engaged in reading relevant literature, I was aided in understanding some themes of research where I could place my work. However, I want to acknowledge that it took approximately 4 years to conceive a research problem situated in my practice. I have been teaching social science to elementary and secondary grades since 2008. For the first two years, I taught in a private school on the outskirts of Delhi, serving a middle-income group population. This school also had a residential facility, and I was a residential teacher. Later, since 2011, I have been teaching in a Delhi Government school, where the majority of the children come from disadvantaged sections of society. In 2018, I switched from my teaching role to assist teachers in improving their teaching. As a mentor teacher, I was given the responsibility of working with more than 500 teachers distributed across 5 schools. For my research work, I chose one of my mentee schools. This is a Co-ed school located in an urban village, Mehram Nagar, near the Indira Gandhi International airport in Delhi. The children come from disadvantaged sections of society, with parents working as house helps, drivers, loaders, and street vendors. The classroom consisted of students from marginalized groups, and my research aims to strengthen their voices.

In this context, I framed certain questions to understand the phenomena of teaching and learning in a social science classroom. In the qualitative research design, the research questions help the researcher navigate through the complexities of the research. Davies & Dodd (2002) argues that qualitative research questions are not meant to produce predetermined results but rather to allow for exploration and understanding of complex phenomena.

Here are my research questions!

- Can children's write-ups be used as an alternative and valid content for teaching-learning social sciences?

- Can this alternative method of teaching social science cope with the traditional examination system?

- Can there be a synergy between what children write and the prescribed curriculum?

- Which are the themes which students feel more comfortable writing about? (To see it in the context of the themes social science curriculum envisages).

- Does this alternative method of teaching and learning empower children to critically look at their world and raise questions?

- How does the relations of power between different participants undergo a change and how does it impinge upon the process of teaching and learning?

- Does this process make the students independent learners?

The work analyses the children's write-ups under larger themes created as per the research questions. The analysis is also triangulated by the field notes and the data related to Focus Group Discussions (FGD). Thus, it unfolds the story of how social science can be taught through a new pedagogy where children write, and teachers discuss their write-ups, bringing students to the centre of the process of knowledge formation. Most policy documents, including NCF (2005) emphasise designing teaching and learning through a constructivist approach, often named as child-centric education, but fail to demonstrate how to actualise this. This study demonstrates how a child centric teaching and learning can be practiced. A major theme explores how to integrate children's write-ups with the existing curriculum. This work accommodates itself to the prescribed curriculum while also going beyond it, opening new possibilities where the curriculum can be expanded with the children's contributions. Chapter three tiled “Framing research or researching to frame; A Teacher researcher's quest for a Methodology in the Classroom Research” talks about the methodology that deals extensively with this issue.

While I write about the findings and recommendations of my research, I am also aware of the larger phenomena that are influencing the world and are determined to impact human life. With advancements in the field of generative Artificial Intelligence, the teaching and learning must be reorganised, and it now seems like a foregone conclusion. Popenici & Kerr, (2017) argues that Artificial Intelligence (AI) has the potential to revolutionise the field of education, transforming the way we teach and learn in schools . If we continue to perceive the role of a teacher as the one who answers questions, perhaps AI will do it more efficiently. Teachers will need to engage with students in the classroom as they collectively pursue knowledge construction. This research is one such reflection, a common pursuit of teachers and students seeking new ways to engage with social science classroom issues.

Media, politics, medicine, and other industries are undergoing significant changes in light of new discoveries in the field of neuroscience. Resource-rich individuals have access to these findings and are utilising them to stay ahead. We cannot exclude the poor and deprived from the findings of this relatively new field in education, as it has broader implications for how we learn. Doidge (2008) discusses the concept of plasticity in neuroscience and suggests that, with a specific set of brain exercises, any child can excel in a particular field by developing a neural pathway or map in the brain. While I may not be familiar with all the brain exercises, writing is certainly a powerful one that is easily accessible to all. Writing is a skill that involves creativity and can be stimulated by engaging both hemispheres of the brain, (Wardiani et al.,2021)

In the aforementioned larger socio-political and technological developments, I place my research. This research essentially involves four crucial components: a teacher with over a decade of experience in the field, students from marginalised backgrounds in elementary classes, a social science classroom, and a daily writing activity. It is essentially the active interaction of these four important components for approximately one and a half years that has resulted in this thesis. This work is the outcome of a prolonged period of engagement in the field. In light of this investigation, I would like to make the following recommendations, which can be linked to the outcomes of this research.

Rethinking Middle-Class Paradigms

A teacher, while teaching about the impact of globalisation on our lives, commented, "Nowadays, our wardrobes are full of clothes. Globalisation has made life easier." She made this statement while teaching a group of students who come from highly marginalised sections of society, and most of them would not have a wardrobe at home. In the word "our" that the teacher used to describe the impact of globalisation as a common experience, these students cannot find their representation. The entire education system, including the administrative functioning of the school, its timetable, curriculum, assessment system, and so on, is designed to suit the middle-class value system. By the term "middle-class value system," I mean that there is an assumption where there is a small family of parents and two children. The house they live in has separate rooms, i.e., a bedroom, kitchen, dining hall, and a hall with a television and a sofa set. It also assumes that parents work in the organised sector where they have limited hours of work, and they enjoy weekends with the family, and so on. Farooqi (2020) brings a closer insight into the lives of these children who come to our school and reveals that the assumptions upon which schools function are not applicable to the children who attend government schools. There is a dire need to document the lives of the children who come to our schools to get a glimpse into their lives and how they don't fit into our middle-class understanding. I have discussed it citing a student's write-up in Chapter One, in Section 1.1 titled "Decolonizing the Process of Knowledge Production." In the write-up, the child writes about how even on holidays like Diwali and Holi, their parents don't get time off from work. Our education policies, which seem to be informed by middle-class values, need to break free from this obsession. They must consider an education system that is embedded in the lived experiences of the children. These lived experiences are diverse, but there is a common thread, especially among children in government schools who come from marginalised sections of society. We cannot continue to offer them an education system primarily designed to accommodate middle-class values. This approach lacks what Bruner (1960) says is “the corresponding language” to effectively communicate with children from marginalised groups, making it difficult for them to remain in the schooling system for an extended period. Through my research, I advocate for an education system that truly represents marginalised groups and serves as an expression of their lived reality. We need an education system that offers them hope and dignity.

The Missing Piece: Advocating for Children's Voices in Education

In a representative democracy, the voice of the people is considered paramount. It is agreed that participants and beneficiaries of a particular policy should design it according to their own requirements. One of the fundamental arguments about local government is that local people should decide the kind of roads they want, the kind of park they want, and so on. The crux is to include the voice of those who are subjugated. The beauty of representative democracy is that it does not dismiss the wisdom of the uneducated masses. Unfortunately, in education, we have failed to make any such space for children. Children are the primary beneficiaries and the most important participants in the education system, and we miss their voice. The Right to Education Act (2010) advocates including their voice in the day-to-day decision-making in a school by bringing them into the School Management Committee, but this has often served as mere tokenism. Including children in the decision-making process holds significant importance in fostering their growth and empowerment. This involvement facilitates the cultivation of critical thinking abilities, an understanding of democratic procedures, and instils a feeling of ownership and accountability regarding their education (Masini,1998). Acknowledged as a fundamental right, children's active participation in decision-making is indispensable for fulfilling their entitlements to education and overall development (Sinclair, 2004). I propose a roadmap, through my research, of how we can actually include children's voices in our decision-making process; children's write-ups are children's voices. The more we include them, the more participatory our education system will become. Currently, adults represent them, and it would not be inappropriate to state that we have failed them. The education system that we have created suffocates them. I believe that when they can express themselves through their own voices, they will be able to help build a better education system. It's time to embrace their voices and trust in their wisdom.

Breaking the Divide: Integrating Research and Teaching in Education

I believe that considering research and teaching as separate activities is a fundamental flaw that needs addressing. Unfortunately, this division persists even at the university level. With the provisions in the New Education Policy (2020) advocating for a separate body for research and ordinary colleges for teaching, it further exacerbates the disconnect between the two. At the school level, these two aspects have never been integrated. My research provides evidence that conducting meaningful research is possible when a researcher is embedded in the field and, at the same time, is also engaged with theories. Theory deeply influences the practice of teaching, and the practice of teaching shapes new theories. By separating the two, we eliminate opportunities for innovation in education.

I strongly propose the removal of constraints imposed by policy and regulatory institutions that prevent teachers from engaging in research. Simultaneously, there should be more affirmative actions that encourage teachers to engage in such research. Some of these affirmative actions could include granting leave to teachers to pursue research, universities implementing preferential policies for admitting teachers into their research programs, the University Grants Commission (UGC) recognizing teaching periods in schools as valid years of experience for teachers' careers, and providing access to library facilities, both offline and online, to all willing teachers, among other measures. Unfortunately, the new education policy (2020) does not make a single reference to research by teachers. Research conducted outside of the school has limited usefulness for teachers in the classroom. If we want our classrooms to evolve and improve, research must be integrated there, and the teacher is one of the most important stakeholders in this process. I have elaborated upon this issue in greater detail in Section 2.10 titled “Beyond the Limitation of Action Research.”

From Representation to Self-Expression: Children's Writing in Curriculum

For whom is the curriculum designed? The common answer to this question across the globe is... Children! Shouldn't we aim to tailor the curriculum to the needs and interests of children? Again, every curriculum claims to do so, but how do they achieve it? They often draw from research that discusses "about children." However, we have not yet developed a mechanism that directly depends on children's voices. While some efforts have been made to capture their voices by involving them in school management committees or organising school parliaments, I believe that children's writing could be the most authentic expression of their world. Currently, they are being represented, but their writing allows them to represent themselves. When reading their writings, I sometimes reflect that these are reflections of their cognition. How they process data in their brains is reflected in their writing. This research opens up a new possibility where we can directly consult children's written work for the development of our curriculum. If practised on a large scale, and if we digitise their writing, it could become one of the finest sources for understanding children, emerging as one of the most authentic resources to shape our curriculum. The vast amount of data we would obtain from digitization can now be analysed by powerful Artificial Intelligence (AI). This research bridges the gap that both teachers and students often experience when implementing a curriculum imposed from above. Through involving students in the curriculum development process, educators have the opportunity to create a learning environment that is both equitable and empowering (Fielding, 2004).

Children's Writing: A Cross-Disciplinary Pedagogic Tool

This culture already exists in schools. In most classrooms, teachers teach a particular chapter from the prescribed syllabus, and children write the questions and answers given at the end of the chapter. Teachers check the notebooks and mark them as correct or incorrect, resulting in a culture that Gardner (1991) has termed the "Correct Answer Compromise." My research offers a slight modification to this established classroom ritual. Currently, teaching influences writing; what I suggest is to allow children's writing to also influence teaching, creating a two-way communication. I believe, and as the research has demonstrated, this simple alteration recognizes children as partners in knowledge production. It has the potential to transform teaching and learning in our classrooms across disciplines.

I have employed this approach in the discipline of Social Science; however, I am confident that it can be equally valuable in a Mathematics class or a science classroom. Children will be able to see mathematics as part of their daily life, which is otherwise presented as a separate world of numbers and symbols. I am not proposing that each teacher should ask students to write a page separately; rather, I am suggesting that each teacher should utilise what a child has written. In an average classroom with 40 students, teachers teaching different subjects should be able to find the write-ups they need, which they can then discuss in their classrooms. Of course, the utilisation of children's write-ups will slowly increase. As more teachers use their write-ups, more children will be encouraged to produce a variety of write-ups. When more teachers collaborate to incorporate children's write-ups into their classrooms, this will become a more manageable task; for one teacher, it could be be overwhelming. I also propose an opportunity for further research in which more teachers come together to make children's write-ups a fundamental part of their pedagogy.

Elevating Children as Knowledge Partners in Education

One of the deepest desires of every human being is to be appreciated for the knowledge they possess. Children are no different; they also crave recognition for their knowledge. Unfortunately, we have often viewed them as empty slates in need of knowledge, but this perspective, championed by empiricists, has been challenged by rationalists. Extensive research now supports the idea that when children enter school, they are already socialised beings with significant knowledge.

Friere (1970) argues for an educational approach that sees children as knowledge partners, advocating for the co-construction of knowledge. In my research, I have embraced this perspective, recognizing children as knowledge partners and utilizing the knowledge they express through writing as valuable content for discussion in the social science classroom. While this approach may be applicable elsewhere, it particularly suits the social science classroom. Social science teaching aims to encourage critical examination of social norms and values, develop a historical perspective, appreciate national diversity, and promote social structures that value equality, justice, and fraternity. In the lived experiences of children, we find references to each of these factors that teachers can discuss with them, elevating children from mere learners to knowers and equal partners in the knowledge construction process. Research worldwide suggests that the classroom should be a space where teachers and students are co-learners, a dynamic that is only achievable when we acknowledge children as knowledge partners. My research has explored this possibility in the context of the social science classroom, opening avenues for further research in other subject areas to test this idea.

Examining the Examination System: A Case for Examination System Reform

Like most research in education, the genesis of this research also aimed to assist students in passing examinations. However, it unfolds to reveal a different narrative. It is no longer merely a strategy proposing that children can pass examinations through daily writing. Instead, it is now a statement about why we need to reform our examination system. This system fails to recognize the diverse abilities our children possess and categorises them as "pass" or "fail," which is detrimental to their growth. Our examination system requires a significant overhaul to capture the nuanced and diverse capabilities of children. Even the NEP (2020) acknowledges this and advocates for a substantial reform in the assessment system.

I do not say that this work did not contribute to helping students pass exams, as there were several other factors determining examination results. Simultaneously, I do not intend to present this work as just another new strategy to help students pass exams. Instead, I reiterate that it offers a compelling argument for why we need to change our examination system. Children who are capable of reflecting on and commenting upon their lived realities, whose write-ups can serve as valid material for classroom discussions, and whose writing challenges the authority of the textbook, reveal that if our examination system fails them, it's not the children who have failed; it's the examination system that has failed itself. It presents a case for reform, but the specific nature of that reform lies beyond the scope of this research, although it provides some broader insights.

Exploring Classroom Power Dynamics: Insights and Implications

In sociology, power is a well-established concept, recognized for its significance in socio-political relations and various aspects of human life. However, when examining the classroom from the perspective of power dynamics, we encounter a notable silence. Particularly in the Indian context, the classroom often appears as a sacred space where questioning is limited. There are norms and rituals that seem unquestionable, and these conventions often position teachers as powerful figures within the classroom, if not as the central figures around whom power relations revolve.

One of the most unique findings of this work is how, through the practice of daily writing, I came to understand my own position of power in the classroom and how it was challenged. It also drew my attention to the power dynamics among different groups of students, influenced by their social, economic, and cultural backgrounds, which often determine their power positions in the classroom.

The underlying question is whether these power relations can be challenged, and, even more importantly, why a teacher should understand and challenge these existing power dynamics in the classroom. A teacher who comprehends power relations within the classroom has a valuable opportunity to create an environment where students from marginalised backgrounds can hold positions of influence. Such an understanding can also enable a student with social privilege to align with marginalised voices in the classroom, fostering a more equitable and inclusive environment. Cook-Sather (2002) further explains that this opens up the possibility for a more equitable and inclusive classroom. In my opinion, it brings to light an essential conversation that is often avoided: the presence of power relations in the classroom and the need to recognize and challenge them.

Writing as a Tool for Independent Learning

The writing exercise that I introduced in the classroom goes far beyond the limited purpose of assisting me in teaching social science. It has the potential to guide students toward independent learning. Rao (2023) beautifully captured the additional possibilities of writing exercises in her blog post titled "Craft and Courage: A Writing Camp in the Himalayas." She writes,

I'm convinced that writing has much bigger, more interesting things it wants to do in our lives than simply get a name onto a book cover.…have also seen a young woman write to heal from an abusive relationship, a grandmother write stories for her newborn grandchild, an empty-nester reconnect with herself through her words, a young man navigate debilitating anxiety and find his way back to formal education through his writing practice, and so many, many people find healing, community, courage, and self-discovery through the written word.

Children from marginalised sections of society have limited institutional support. The dropout rate at the secondary level of schooling is approximately 50%, with a conversion rate(College going age, 18-23) of around 28%. These children have few opportunities to receive support from institutions, leaving them with the need to develop the habit of independent learning. While various tools may be available, writing stands out as the most affordable and accessible tool accessible to every student. Through this research, I argue that this exercise should be viewed as a process that helps students become independent learners. When they are part of a school, they have institutional support, but if they cultivate the habit of writing, they can continue to thrive as learners even in the absence of such support.

Breaking the Copy Culture

One of the surprising findings of this research has been the close examination of the "copy culture" in schools. In my analysis, this culture is responsible for a significant number of failures. If we can address this issue, we will be better equipped to tackle the question of how to promote more students to the next grade. Currently, ensuring students pass examinations seems to be a primary concern for most education departments. Through this research, I propose that if we eliminate copying in the classroom throughout the year, we can achieve this goal.

What is required is a bit more time for teachers and proper orientation, emphasising that students' notebooks should not consist of mere "copy work." In each subject, when teachers request the completion of the notebook, they must ensure that it contains original writing by the children, not copied and pasted from textbooks or other sources. This simple adjustment can transform students. If they learn how to write originally, and if our examination system embraces original writing, it will become nearly impossible for children to fail in exams. I have discussed this phenomenon in detail in Section 8.7 titled "The Culture of Copy Work."

Conclusion

We are a part of a knowledge society. The knowledge that is essential for survival and leading a dignified life has been passed down through generations. Some of this knowledge is accessed through literature, culture, norms, traditions, and so on. What I have been able to contribute to this flow of knowledge is based on the vast body of knowledge produced by scholars before me. Building upon their work, I have added a new dimension to it.

Among the various fields of knowledge production aimed at enhancing human understanding of life and its meaning, the discipline of Education is relatively new. Within the discipline of Education, knowledge related to school education is considered a phenomenon of industrial society and is relatively new in the history of human existence. This is one reason why our understanding of schooling is limited, and this field requires intense engagement from scholars around the world.

Teachers, as one of the primary constituents of school education responsible for facilitating learning, can also be entrusted with the responsibility of conducting research. In this context, I present my research, which is focused on a social science classroom in a government school in Delhi. After 15 years of intense engagement with this field, including the last 6 years as a PhD research scholar, I have proposed certain findings and recommendations through my research.

I argue why it is essential for us to contextualise the experience of schooling within the lived realities of children and break free from the middle-class value system that seems to dominate our school education. I further argue that we need to acknowledge the voices of children in shaping our education system. We have failed them, and it's time we include them in the development of a system in which they are active participants.

I propose a mechanism for including their voices through children's writing, which can be utilised to develop curriculum content across various disciplines. This can also inform pedagogy, and I demonstrate in this research how I have applied it in social science teaching. My ability to articulate these ideas as a teacher is a result of my engagement with research, and I strongly argue for the engagement of teachers in research.

A teacher who is also a researcher, and students who write, create a classroom that challenges the power dynamics within the classroom. I have delved deeply into this phenomenon in my research and argued how an understanding of power dynamics in the classroom helps teachers accommodate diversity and ensure equity. This entire process leads to one of the most desired skills of our time: becoming an independent learner. We cannot facilitate the growth of independent learners unless we discontinue the "copy culture" that hinders the teaching and learning process. Therefore, I present comprehensive findings suggesting how we can overhaul the teaching and learning experiences. While my research is limited to a social science classroom, I believe its implications can extend beyond this specific context.

References

Cook-Sather, A. (2002). Authorizing students’ perspectives: toward trust, dialogue, and change in education. Educational Researcher, 31(4), 3-14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x031004003

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291-309. doi:10.1080/02619768.2017.1301814

Davies, D. and Dodd, J. (2002). Qualitative research and the question of rigor. Qualitative Health Research, 12(2), 279-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230201200211

Doidge, N. (2008, August 7). The Brain That Changes Itself. Penguin UK.

Farooqi, F. (2020). Ek School Manager Ki Diary [A School Manager’s diary]. Eklavya.

Fielding, M. (2004). Transformative approaches to student voice: theoretical underpinnings, recalcitrant realities. British Educational Research Journal, 30(2), 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000195236

Frank, R. (2017, November 14). Richest 1% now owns half the world's wealth. CNBC. Retrieved October 7, 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/14/richest-1-percent-now-own-half-the-worlds-wealth.html

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Masini, E. B. (1998). Children's participation: the theory and practice of involving young citizens in community development and environmental care. Land Use Policy, 15(2), 176-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0264-8377(97)00006-9

Moreira, C., Diversi, M. (2022). Border Smugglers: Betweener Bodies Making Knowledge and Expanding the Circle of Us. In Adams, E. Tony, Jones, Holman, Stacy & Ellis, Carolyn (Eds.), Hand book of Autoethnography (2nd ed., p. 89). Routledge.

Popenici, S. and Kerr, S. (2017). Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-017-0062-8

Rao. (2023, October 5). Craft and Courage: A Writing Camp in the Himalayas. Aditirao.Net. Retrieved October 7, 2023, from https://aditirao.net/events/craft-and-courage-october-2023

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14. doi:10.3102/0013189X015002004

Sinclair, R. (2004). Participation in practice: making it meaningful, effective and sustainable. Children &Amp; Society, 18(2), 106-118. https://doi.org/10.1002/chi.817

Wardiani, R., Mulyaningsih, I., & Maneechukate, S. (2021). Writing skills development: a balancing perspective of brain function in elementary schools. Al Ibtida Jurnal Pendidikan Guru Mi, 8(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.24235/al.ibtida.snj.v8i1.7795

The thesis is available at

https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in:8443/jspui/handle/10603/591031

- Log in to post comments