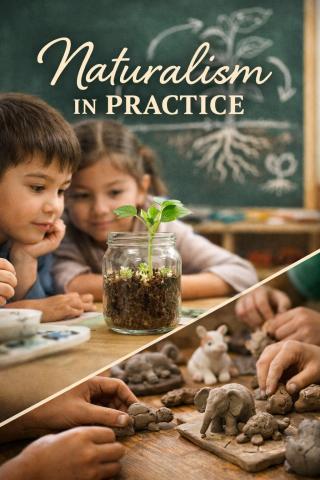

Naturalism in Practice

A student-teacher noted this in her reflective diary:

“Today was a hands-on day. We moved away from the textbooks and focused on Environmental Science (EVS). We talked about the life cycle of plants, and I brought in some soaked seeds so the students could see the sprouts beginning to emerge. During the activity period, we did clay modeling. I asked the students to sculpt their favorite animals. The classroom was quiet for once, as everyone was deeply focused on their little masterpieces. We ended the day with a show and tell, where each child explained why they chose their animal. It’s amazing how much they open up when they are creating something with their hands.”

What is interesting to note here is that she is explaining how a plant grows, and in another activity, children are engaged in sculpting. What is happening here is actually an example of Naturalism in education—quietly, almost unknowingly. Yet, when Naturalism appears as a question in their exam, students often feel nervous. Some who have memorised the definition manage to write something, many fumble.

What Mathematics is for most students in school education, Philosophy becomes for students of education—a tough subject. The fear is similar, the anxiety familiar, and the confusion equally real.

Concepts like Idealism, Pragmatism, Naturalism, Empiricism, Rationalism, and so on, are words that threaten them the most. While they memorise the definition of one, they start mixing it with another after a while. Their understanding of these isms is not as clear as the difference between a table and a chair. Somewhere along the way, ideas meant to explain practice become detached from it. There is no doubt that these are abstract concepts and require serious engagement to be understood properly. But perhaps the question we need to ask is this: why do ideas that explain our daily teaching feel so distant when they appear on paper? Nevertheless, here I will try to explain Naturalism—not through definitions, but through classroom practice.

If we look closely at the activities we perform in classrooms, we can often connect them to one or the other school of philosophy. Interestingly, most classrooms present examples where we can see the underplay of multiple schools of philosophy at work. This is not because different teachers consciously follow different philosophies. At times, the same teacher, within the same day, engages in activities that can be traced back to different philosophical backgrounds. We can think of it like a child in a park trying different kinds of swings. All are swings, yet each may be designed using different principles of mechanics and physics. The experience feels seamless to the child, even though the principles behind them differ.

Let us return to the example we began with. Children observe how a plant grows from a seed. They are watching, touching, noticing change over time. In the second activity, they are shaping clay, learning by doing, discovering form through their hands. And when the teacher reflects on the joy of creation, she is pointing towards an idea—something that emerges from the mind.

The first two clearly lie within Naturalism. The last reflects a trait of Idealism. A single classroom moment, then, rarely belongs to one philosophy alone.

Idealism believes that whatever we make sense of in the world originates in the mind. Naturalism, on the other hand, explains the world in terms of nature and natural laws. Water flows from top to bottom—that is a law of nature. Similarly, much of what we understand and experience can be explained through the natural world around us.

In education, Naturalism places the child at the centre of the teaching–learning process. The teacher becomes a guide rather than a controller. Learning connects with real life, and emphasis is placed on observation, experimentation, and activity. Naturalism also holds that nature is the ultimate reality, that humans are biological beings, that knowledge comes from sense experience, and that education should follow the child’s natural development.

Now, referring back to the classroom scene we began with, one may pause and ask: if this is Naturalism in practice, unfolding so naturally in everyday teaching, why does it feel so difficult when it appears as a definition in an exam?

- Log in to post comments