Beginning from the Self: Experiments with Auto-Ethnographic Speaking

Over the last few years, my engagement with classrooms and teacher groups has slowly pushed me to experiment—not with content, but with form. I have been asking a simple question: How does one speak about structural issues in education without beginning from abstraction? Increasingly, my answer has been to begin with the self. I have started calling this auto-ethnographic speaking—a style where personal narrative is not an anecdote added at the end, but the starting point through which larger socio-political and educational questions are introduced. I reflected on this recently after a session with students, where I noted that I now instinctively “tell a story and embed larger socio-political-cultural issues within it

Instead of beginning with ideas like inequality, merit, or access, I began with my schooling. In the session, I said (translated from Hindi):

“Back then, unfortunately, schools existed, but there were no teachers. The situation was the same in colleges. We would simply take the exams and move to the next grade. As a result, students were entirely dependent on private tuitions. Even today, if you look at the system for educating poor children across India, it remains the same—just taking exams and getting promoted. The shortage of teachers persists. I am specifically referring to schools where children from common, impoverished households study. Even where teachers are available, the government keeps them entangled in other tasks. They conduct censuses, perform election duties, and are involved in countless other administrative chores; they are not utilized for teaching. Initially, I thought this only happened in Bihar, but now that I am doing research, I realize the situation is the same in Rajasthan, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra. I have witnessed this first-hand in many places.

In Bihar, at least there was the advantage of schools being nearby, right in the village. But when I visited the North-East, I found high schools are as far as 15–20 km away. This essentially means that education for girls ends right there. If a village only has a school up to the 5th grade and nothing beyond that, their schooling stops. In Madhya Pradesh, just 20 km from Bhopal, I visited a tribal village where the school went only up to the 5th grade, and the high school was 8 km away. In such circumstances, a girl's education comes to an end.

From the last decade of the previous century until now, continuing education has become an extreme challenge for children from poor families and especially for girls across India. Only a few manage to move forward. While I was studying, for a long time I believed that it was a matter of 'merit'—that those who are bright will succeed. Many of you might believe the same.

However, as I research more, I have come to realize that merit is essentially 'privilege.' Let me explain this with an example: I was able to complete my studies because, despite the lack of school teachers, I had access to tuition and could afford the fees. Many other children studying with me probably couldn't afford that. In a class of 100 students, only about 20 could move ahead, while the rest failed or dropped out. At the surface level, it appears to be merit, but at its core, it is privilege. Only those who have resources and access actually end up being 'meritorious.

Talking about my exposure to regular college, I shared

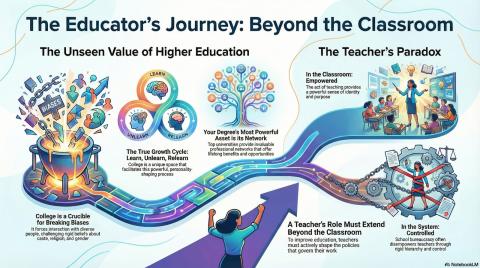

That was my first real experience of college—attending classes, interacting with such a diverse range of people, observing them, and understanding different perspectives. I notice a growing trend today where students are eager to pursue 'distance learning' after the 12th grade so they can work simultaneously and support their families. However, I believe that receiving a college education in 'regular mode' is essential. The precise reason is that the purpose of college is not merely to teach you a subject or explain a concept; its true objective is to create an atmosphere where you encounter, converse, and engage with people who are different from you.

We are all raised within specific families and social circles, which often leads us to blindly follow certain beliefs, traditions, and systems. We frequently become so 'rigid' that we start believing—'my religion is the best,' 'my caste is superior,' or 'my language is the most amazing'—and that no one else can possibly compare. These biases only shatter when you spend time with people outside your bubble. From a distance, these walls do not break; they only grow stronger.

College is that space where you sit together over tea, work on assignments, prepare for exams, or rehearse for a skit. When you meet on the sports field, conversations spark. It is during these interactions that our internal biases—whether regarding gender, caste, or a narrow worldview—surface. When someone challenges those views, it might feel uncomfortable at first, but that is exactly where change begins. In that environment, three things happen very gradually yet powerfully: Learning, Unlearning, and Re-learning. This is a subtle process that plays a vital role in shaping our personality. Schools often fail to provide this opportunity because they usually follow the 'neighbourhood schooling' model, where most children come from similar economic and social backgrounds.

In contrast, a college or university is a hub of diversity. There, a student from Bihar might meet someone from Tamil Nadu, Kashmir, or Manipur. A boy from a traditional family might interact with a girl with modern outlooks, or a girl raised in Delhi might meet a boy from a deeply traditional background. These conversations break the rigidity we inherited from our families and society. This is why I feel it is extremely important for every student to try and attend a regular college for at least three years. As far as academic learning is concerned, that can be accessed from anywhere today. But the experience a college campus offers cannot be found elsewhere. College is not just about adding a degree to your CV; it is the place where your values and your personality are forged.

However, I am also aware of the limitation of this approach of speaking. Not everyone is comfortable sharing personal histories. For some, stories can be misread, judged, or even used against them. This method cannot be universalised without sensitivity. In the end this experiment of bringing what I know to who I am, is also a matter of privilege, and I am aware of it.

- Log in to post comments